In a rapidly evolving marketplace, two forces have emerged as dominant yet seemingly contradictory: premiumization and sustainability. Premiumization reflects the global consumer’s desire for exclusivity, quality, and distinction in products and services. From craft, spirits and artisanal foods to luxury automobiles, personal care products and high-end fashion, the trend demonstrates a shift from mass consumption to more curated, premium experiences (Deloitte, 2021). In emerging markets like India, the consumer ecosystem is being redefined by the Gen-Z, fueling premiumization. 60% of the commerce transactions are accounted for by the affluent middle class, who are steadily increasing in the Tier II and III cities of an emerging market (Deloitte, 2025, Forbes India, 2025). On the other hand, sustainability represents the urgent need to reduce environmental impact, promote circular economies, and ensure that consumption and production patterns remain within planetary boundaries (UNEP, 2022).

The question that arises is profound: Can premiumization be reconciled with sustainability, or does the pursuit of exclusivity inevitably undermine environmental goals? This blog explores this dynamic, highlighting convergences, contradictions, sectoral impacts, and the future trajectory of premiumization in relation to sustainability.

Understanding Premiumization

Premiumization is not just about higher price tags; it is about creating added value through quality, authenticity, storytelling, and experience. Consumers increasingly seek products that represent more than functionality—they want items that embody meaning, prestige, and identity (Graham et.al, 2019; Kapferer & Valette-Florence, 2018).

Several factors that drive this trend:

1. Rising Incomes and Aspirational Lifestyles: The growth of emerging middle classes in regions such as Asia, Africa, and Latin America is reshaping global consumption patterns. With increasing disposable incomes, consumers are moving beyond basic needs and seeking products that reflect their aspirations, success, and upward mobility. Premium brands, therefore, become vehicles for self-expression and lifestyle enhancement (Kumar, Paul, & Unnithan, 2020)

2. Status Signaling: Consumption often extends beyond functionality and enters the realm of symbolism. In many societies, premium products are used as social markers, signaling wealth, sophistication, and distinction. Such goods allow individuals to reinforce their identity and communicate belonging or superiority within social hierarchies (Han, Nunes, & Drèze, 2010).

3. Quality and Experience: Premiumization is not limited to price; it also reflects a shift in consumer priorities toward craftsmanship, authenticity, and immersive experiences. Consumers increasingly value durability, attention to detail, and uniqueness—qualities that set premium offerings apart from mass-market commodities. This pursuit of “something more” strengthens brand loyalty and enhances perceived value (Yeoman, 2011).

4. Conscious Consumption: The definition of “premium” is expanding to include ethical and sustainable dimensions. Health-conscious and environmentally aware consumers are gravitating toward products that are “better for me” and “better for the planet.” Premium brands that emphasize wellness, transparency, and sustainability are not only meeting consumer expectations but also positioning themselves as responsible contributors to broader social and environmental goals (Accenture, 2018).

Industries from food and beverages to hospitality and personal care are reorienting strategies around premium segments, betting that consumers will continue trading up for authenticity and value.

The Sustainability Imperative

Sustainability is no longer optional. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and rising consumer awareness have created pressures on businesses to act responsibly. Studies show that 73% of global consumers are willing to change their consumption habits to reduce environmental impact (Nielsen, 2019). Governance across the globe, too are tightening regulations around carbon emissions, packaging, and waste management.

Three pillars define sustainability (Purvis, Mao & Robinson, 2019):

1. Environmental: Reducing ecological footprints through renewable energy, resource efficiency, and sustainable sourcing.

2. Social: Ensuring fair labor practices, diversity, and community engagement.

3. Economic: Building resilient, long-term value chains rather than focusing on short-term profits.

Premium brands, which already emphasize exclusivity and differentiation, appear well-positioned to integrate sustainability into their DNA. Yet, challenges remain.

Points of Convergence: Premiumization Meets Sustainability

Despite potential tensions, there are strong areas of overlap where premiumization and sustainability reinforce each other:

1. Durability and Longevity

Premium goods are typically crafted with superior materials and meticulous attention to detail, which enhances their durability and extends their lifecycle. A luxury handbag, high-end watch, or premium automobile often outlasts mass-market counterparts, reducing the frequency of replacements. This inherently aligns with sustainable principles by minimizing waste generation and curbing the culture of disposability. Longevity thus becomes both a marker of exclusivity and a pathway to environmental responsibility (Lumina,2024).

2. Authentic Storytelling

In an era where consumers demand greater accountability, transparency around sourcing, production processes, and labor practices is becoming integral to brand value. Within the premium segment, authenticity is itself perceived as a luxury. Brands that can credibly communicate their sustainability journey—through traceable supply chains, heritage narratives, or ethical certifications strengthen consumer trust while elevating the brand experience. Sustainability here is not an add-on but a core component of the luxury promise (Hanhimäki, 2025).

3. Innovation Leadership

Premium markets often serve as laboratories for sustainability-driven innovation. High-end brands can absorb the costs of pioneering eco-friendly materials, circular design models, and carbon-neutral operations, setting benchmarks that eventually diffuse into the mass market. Tesla, for instance, reframed electric mobility as a luxury aspiration before catalyzing its mainstream adoption. Similarly, premium fashion and hospitality brands are experimenting with bio-fabrics, regenerative sourcing, and closed-loop ecosystems that later inspire broader industry shifts (Mangram, 2012).

4. Experiences over Ownership

A notable trend in premiumization is the pivot from material goods to transformative experiences. Offerings such as eco-tourism, wellness retreats, or fine dining rooted in zero-waste principles embody exclusivity while reducing material consumption. By emphasizing access, immersion, and emotional value over ownership, premium brands can align with sustainable consumption models while still catering to aspirational lifestyles (Lumina, 2024; Yeoman, 2011).

Points of Contradiction: Where Tensions Arise

While synergies exist, contradictions challenge the alignment of premiumization with sustainability:

1. Resource Intensity: Many premium products are built on the use of rare, exotic, or non-renewable resources, which raises ecological and ethical concerns. For instance, rare leathers, precious gemstones, and other luxury raw materials often entail destructive extraction processes, biodiversity loss, and questionable labor practices. The very exclusivity of such materials may conflict with principles of ecological balance (Siu, 2025).

2. Carbon-Heavy Supply Chains: To enhance exclusivity and global prestige, premium brands frequently rely on international sourcing networks. While this global reach strengthens brand storytelling, it also extends transportation routes, increasing carbon footprints across production, distribution, and after-sales service. The pursuit of rare ingredients or components often comes at the expense of environmental efficiency (Dohale et. al, 2024).

3. Over-Packaging: Premiumization often equates to elaborate and ornate packaging designed to signal exclusivity—such as wooden chests, heavy glass bottles, or metallic finishes. While aesthetically appealing, such practices contradict efforts toward waste reduction, recyclability, and circularity. Over-packaging remains one of the most visible points of tension between luxury branding and sustainability (Thomas et. al, 2023).

4. Exclusivity vs. Inclusivity: By definition, premiumization emphasizes exclusivity, which risks making sustainability accessible only to affluent consumers. If environmentally friendly products remain positioned as luxury goods, their broader societal and systemic impact becomes limited. This exclusivity may inadvertently reinforce inequalities in sustainable consumption, slowing down the transition to mass-market adoption (Goedertier, Weijters, & Van den Bergh, 2024).

These contradictions underscore the complexity of reconciling exclusivity with environmental responsibility.

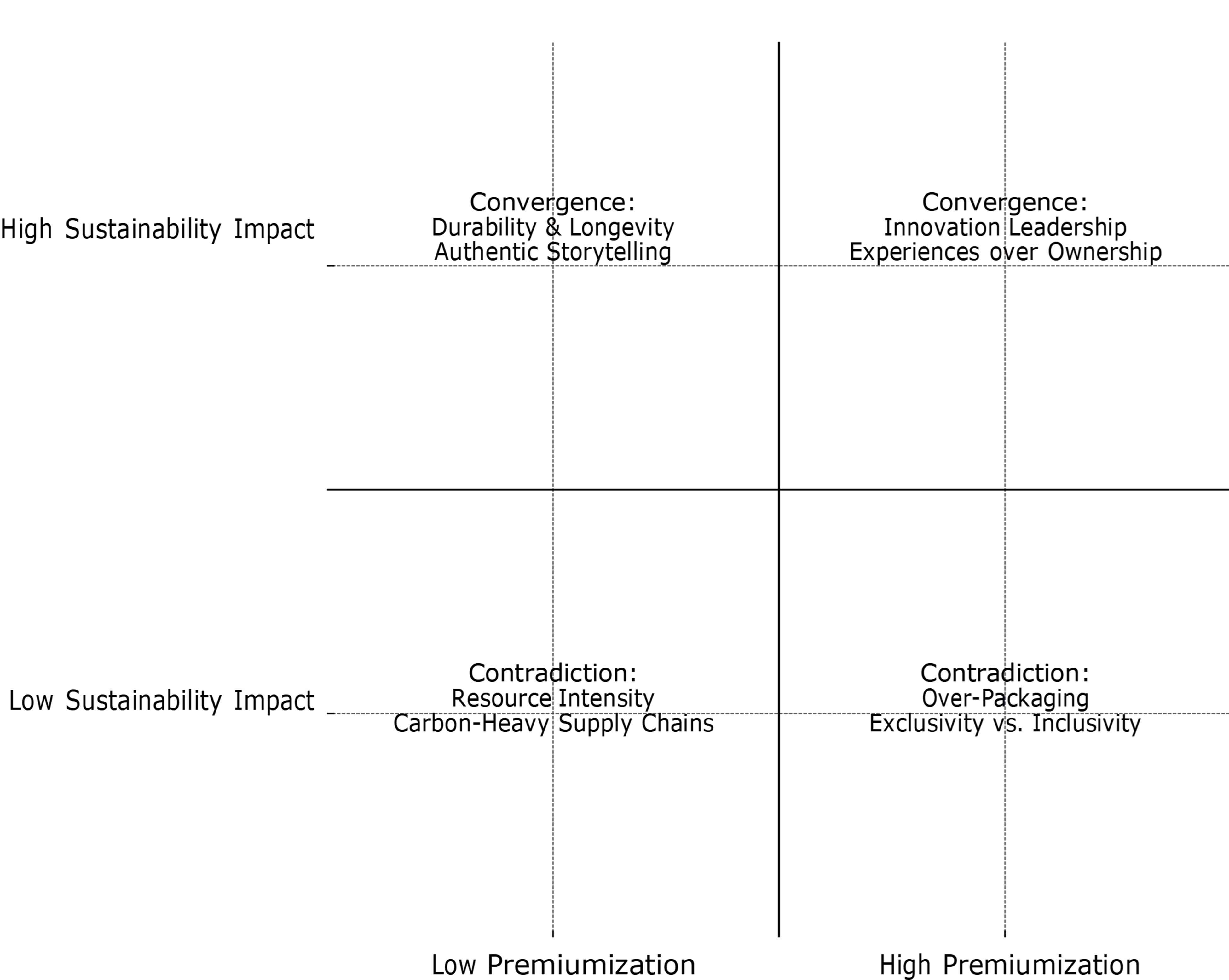

The following matrix illustrates the areas where premiumization supports sustainability and where it creates tensions.

Figure.1

Source: Author’s visualization of the concepts

Sectoral Perspectives

Fashion

Luxury fashion has been criticized for waste, yet it is also leading the slow fashion movement. Brands like Stella McCartney emphasize cruelty-free materials and circularity, while others adopt resale and repair services. Premium consumers increasingly demand sustainability alongside exclusivity (Wells et.al, 2021; Shu, 2025).

Food & Beverages

Premiumization in F&B often aligns with sustainability—organic produce, fair-trade coffee, plant-based alternatives, and locally sourced ingredients. However, exotic “superfoods” flown across continents highlight contradictions between premium health trends and ecological impact with over sourcing and dependance on carbon heavy supply chains (Tikkha, Agarwal & Rajwanshi, 2024).

Automobiles

Premium auto brands are at the forefront of the EV revolution. Tesla, BMW, and Mercedes-Benz frame electric mobility as aspirational, creating a halo effect that normalizes sustainable transport. Yet, concerns around battery mining and resource use remain unresolved (Murdock et. al., 2021).

Hospitality

Premium hospitality increasingly markets sustainability as luxury—eco-resorts, carbon-neutral lodges, and slow travel experiences. Here, sustainability is not a compromise but part of the elevated offering (Hindley, van Stiphout & Legrand, 2023).

Consumer Goods

From beauty to home care, premium segments highlight natural ingredients, biodegradable packaging, and ethical sourcing. Premium beauty brands like Gucci, Stella McCartney, L’Occitane and Aveda have embedded sustainability in their brands DNA (Alghanim & Ndubisi, 2022).

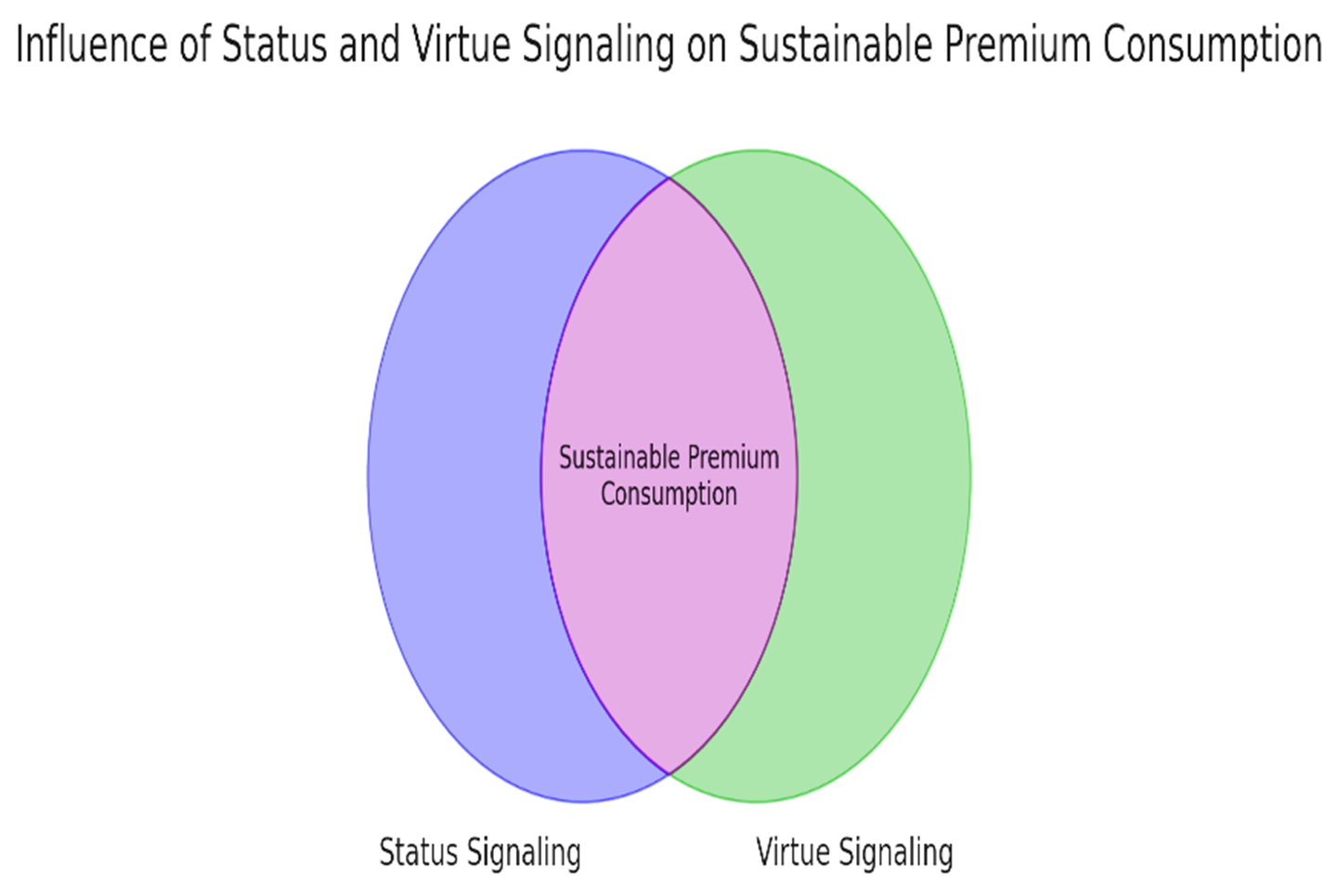

Consumer Psychology: The Green Premium

Consumers are not just buying products—they are buying identities and values. Research shows that luxury consumption is often motivated by status signaling (Han, Nunes, & Drèze, 2010). In the sustainability context, this manifests as “virtue signaling,” where consumers use eco-premium products to demonstrate ethical responsibility (Griskevicius, Tybur, & Van den Bergh, 2010).

However, the “green premium” poses barriers. Many consumers are unwilling or unable to pay higher prices for sustainable goods, limiting market penetration (Nielsen, 2019). Premium brands face the challenge of ensuring sustainability does not remain a status symbol restricted to the affluent.

Figure 2: Consumer Psychology in Premium Sustainability

The Venn diagram shows how status signaling (blue) and virtue signaling (green) influence sustainable premium consumption (purple overlap). It is adapted from Han, Nunes, & Drèze (2010) and Griskevicius, Tybur, & Van den Bergh (2010) and conceptualized by the Author.

Business Strategy Implications

For brands, the intersection of premiumization and sustainability is not merely a challenge but an opportunity to reimagine long-term competitive advantage. Strategic innovation is key to reconciling exclusivity with responsibility.

1. Integrate Circular Economy Models: Premium brands can leverage their emphasis on durability to introduce circular practices such as resale platforms, recycling initiatives, and repair services. These not only extend product lifecycles but also reinforce exclusivity by offering curated, heritage-driven ownership experiences (Niedenzu, 2022; Lumnia, 2024).

2. Transparency as Luxury: In premium markets, transparency itself can be framed as a form of exclusivity. Full traceability of raw materials, carbon footprint labeling, and credible ethical certifications elevate brand credibility and align sustainability with luxury storytelling (de Boissieu et. al, 2021).

3. Experience-Driven Value: Rather than treating sustainability as a mere attribute, brands can weave it into holistic experiences. Eco-tourism packages, sustainable fine dining, carbon-neutral events, or wellness retreats create immersive encounters that add emotional and symbolic value while reducing reliance on material consumption (Lumina, 2024; De Boer, 2003).

4. Collaborations and Partnerships: The scale of sustainability challenges often exceeds the capacity of individual firms. Premium brands can enhance their legitimacy and impact by collaborating with NGOs, governments, academic institutions, and tech innovators. Such partnerships can accelerate the adoption of eco-materials, renewable energy solutions, and community-focused initiatives (Schweitzer & Meng, 2023; Mariani et. al., 2022).

5. Democratization Pathways: Premium markets often serve as incubators of innovation, but long-term systemic change requires diffusion. What begins as an exclusive sustainable practice—be it circular design, bio-based materials, or ethical sourcing—must eventually filter down into the mass market. By enabling democratization, premium brands can reinforce their pioneering status while expanding societal impact (Christodoulides & Wiedmann, 2022).

Prognosis: The Road Ahead

The relationship between premiumization and sustainability is dynamic, evolving across different time horizons. A phased view helps clarify the trajectory of change.

Short Term (1–3 years)

Premium brands will intensify their experimentation with eco-materials, carbon-neutral operations in supply chain, and sustainability-centered storytelling. In this phase, sustainability will primarily serve as an exclusivity marker, enhancing differentiation in luxury markets and reinforcing brand prestige.

Medium Term (3–7 years)

As technologies mature and economies of scale improve, sustainability innovations originating in premium markets, such as biodegradable materials, closed-loop supply chains, and electric mobility, will begin to diffuse into mainstream consumer segments. This trickle-down effect will help reduce costs and broaden accessibility, gradually shifting sustainability from a niche value proposition to a more standard expectation globally.

Long Term (7+ years)

The ultimate test for premium sustainability lies in democratization. If sustainable practices remain confined to affluent consumers, they will fall short of addressing systemic global challenges. The long-term prognosis suggests a redefinition of luxury itself: moving away from conspicuous consumption toward responsibility, stewardship, citizenship and collective well-being. In this scenario, the highest form of exclusivity may lie not in ownership of rare goods but in enabling practices that make sustainability both aspirational and accessible to all. The following timeline outlines the short, medium, and long-term future of premiumization and sustainability.

Figure 3: Prognosis Timeline for Premiumization & Sustainability

Source: Author’s conceptualization of the timeline

Conclusion

Premiumization and sustainability are frequently cast as opposing forces—one rooted in exclusivity and status, the other in inclusivity and shared responsibility. However, their intersection reveals a more complex and interdependent relationship. Premiumization has the capacity to act as a catalyst for sustainable transformation by pioneering innovations, shaping consumer aspirations, and reframing environmental and ethical responsibility as symbols of prestige.

Yet, this potential is shadowed by contradictions: reliance on resource-intensive materials, carbon-heavy supply chains, and the risk of positioning sustainability as an elitist privilege. For the promise of premium sustainability to be realized, these tensions must be addressed through circular models, transparency, partnerships, and democratization pathways.

The trajectory ahead is clear. The future of premiumization will not be defined by excess but by responsibility. The most successful brands will be those that elevate sustainability into the realm of ultimate luxury—making it not only desirable and authentic, but also accessible and universal. In this redefinition, luxury and sustainability converge, offering both market differentiation and societal value. Importantly, such an approach directly contributes to advancing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those linked to responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), and reduced inequalities (SDG 10).

References

Accenture. (2018). To Affinity and Beyond. The rise of purpose-led brands: Navigating the shift from me to we. Accenture Strategy.

Alghanim, S., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2022). The paradox of sustainability and luxury consumption: The role of value perceptions and consumer income. Sustainability, 14(22), 14694.

Christodoulides, G., & Wiedmann, K. P. (2022). Guest editorial: a roadmap and future research agenda for luxury marketing and branding research. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(3), 341-350.

De Boer, J. (2003). Sustainability labelling schemes: the logic of their claims and their functions for stakeholders. Business Strategy and the Environment, 12(4), 254-264.

de Boissieu, E., Kondrateva, G., Baudier, P., & Ammi, C. (2021). The use of blockchain in the luxury industry: supply chains and the traceability of goods. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(5), 1318-1338.

Deloitte. (2021). Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2021. Deloitte Insights.

Deloitte. (2025). India’s US$1.06 trillion retail sector is set to reach $1.93 trillion by 2030. Deloitte-FICCI report

Dohale, V., Ambilkar, P., Mangla, S. K., & Narkhede, B. E. (2024). Critical factors to sustaileanant innovations for net-zero achievement in the manufacturing supply chains. Journal of Cleaner Production, 455, 142295.

Forbes India. (2025). Premiumization in India: Industry playbook and cultural imperatives. ESSEC Business School, Expert Opinions and Industry Insights. ESSEC Business School | Expert Opinions & Industry Insights | Forbes India Blog

Goedertier, F., Weijters, B., & Van den Bergh, J. (2024). Are consumers equally willing to pay more for brands that aim for sustainability, positive societal contribution, and inclusivity as for brands that are perceived as exclusive? Generational, gender, and country differences. Sustainability, 16(9), 3879.

Graham, C., Nenycz-Thiel, M., Dawes, J., & McColl, B. (2019). Premiumisation strategy as a way to grow. Admap Magazine.

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., & Van den Bergh, B. (2010). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404.

Han, Y. J., Nunes, J. C., & Drèze, X. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: The role of brand prominence. Journal of Marketing, 74(4), 15–30.

Hanhimäki, O. (2025). Authenticity in sustainable branding and its effect on consumers trust and loyalty.

Hindley, C., van Stiphout, J., & Legrand, W. (2023). Luxury hospitality and sustainability: An oxymoron or viable pursuit?. In Advances in Hospitality and Leisure (Vol. 19, pp. 3-23). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Kapferer, J. N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2018). The impact of brand penetration and awareness on luxury brand desirability: A cross country analysis of the relevance of the rarity principle. Journal of Business Research, 83, 38–50.

Kumar, A., Paul, J., & Unnithan, A. B. (2020). ‘Masstige’marketing: A review, synthesis and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 113, 384-398.

Lumina, R. (2024). The premiumization opportunity: enhancing Italian SMEs value proposition through three dimensions.https://unitesi.unive.it/bitstream/20.500.14247/23536/1/898805-1292958.pdf

Mangram, M. E. (2012). The globalization of Tesla Motors: a strategic marketing plan analysis. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 20(4), 289-312.

Mariani, L., Trivellato, B., Martini, M., & Marafioti, E. (2022). Achieving sustainable development goals through collaborative innovation: Evidence from four European initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(4), 1075-1095.

Murdock, B. E., Toghill, K. E., & Tapia‐Ruiz, N. (2021). A perspective on the sustainability of cathode materials used in lithium‐ion batteries. Advanced Energy Materials, 11(39), 2102028.

Niedenzu, D. (2022). Transforming Linear to Reuse Circular Supply Chains (Doctoral dissertation).

Nielsen. (2019). The Database. The business of Sustainability. Nielsen Global Survey.

Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability science, 14(3), 681-695.

Schweitzer, F., & Meng, Y. (2023). How collaborating with NGOs makes green innovations more desirable. Business & Society, 62(2), 363-400.

Shu, E. (2025). Behind the runway: managing paradoxical tensions on sustainable luxury. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(2), 5421-5433.

Siu, M (2025). Reinventing Ultra-Fast Fashion: Strategic Growth Recommendations for SHEIN's Sustainable Brand Development. Open Journal of Business and Management, volume 13, issue 04, 2025[10.4236/ojbm.2025.134154], Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5274471 or http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2025.134154

Thomas, J., Patil, R. S., Patil, M., & John, J. (2023). Addressing the sustainability conundrums and challenges within the polymer value chain. Sustainability, 15(22), 15758.

Tikkha, V., Agarwal, P., & Rajwanshi, R. (2024). Assessing greenwashing practices with special relevance to the food & beverage industry. International Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Research, 10(4), 472-492.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). (2022). Sustainability and circularity in consumption and production. UNEP Report.

Wells, V., Athwal, N., Nervino, E., & Carrigan, M. (2021). How legitimate are the environmental sustainability claims of luxury conglomerates? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 25(4), 697-722.

Yeoman, I. (2011). The changing behaviours of luxury consumption. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 10(1), 47-50.

Copyright © 2025. Rajagiri Business School. All Rights Reserved. Website Designed and Maintained by Intersmart